“I wish it need not have happened in my time," said Frodo.

"So do I," said Gandalf, "and so do all who live to see such times. But that is not for them to decide. All we have to decide is what to do with the time that is given us.”

― J.R.R. Tolkien, The Fellowship of the Ring

Here in central Texas, I’ll admit that I’m of two minds heading into the dog days of summer. On the one hand, I am excited that July is underway: I get my family back from Alaska, where my wife’s family is from, and I am anxious to see my kids, who are soon returning from their annual jaunt to the north country, where they hike, fish, camp, and just have a ball with their grandparents in the beautiful Alaskan wilderness. We’re only a week removed from 4th of July celebrations, Hill Country trips, and maybe a run down to the Texas coast to wave to Rockport or Galveston …

And yet, it was a tough June, and July began in a similarly ominous fashion. The paper’s headline reads that we are “imprisoned” by 100-degree days, which feels spot-on; we nearly matched our record of consecutive triple digit days here in Austin, and Dallas and Houston can say similar things. Our fellow Texans in the Panhandle and in West Texas are in even more dire straits, with exceptional drought cropping up in many parts of the state. Almost 20 million Texans are estimated to be in a drought-stricken area as of this writing.

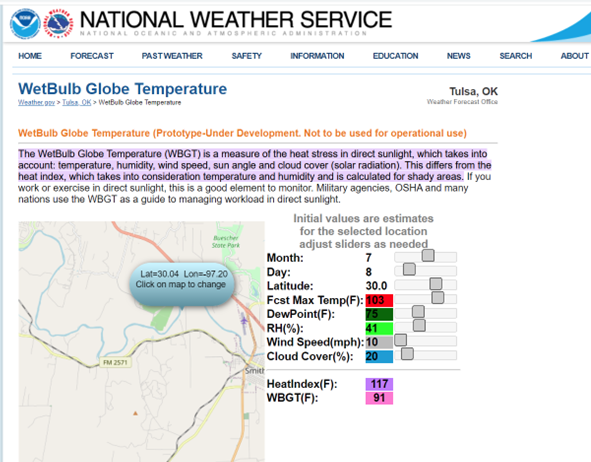

When I’m not in front of a computer, or zooming away, or meeting with stakeholders across the state, I try to spend a fair amount of my free time outside. One thought riddled my mind this month as I dragged my 41-year old carcass around in the triple digit heat: how are we even going to do this? How are the folks in construction, or agriculture, for example, going to thrive and produce with 40 more days annually of triple digit heat? Pollution is expensive. The 2011 drought cost Texas farmers some $7B in losses. Those numbers will trend upward. By some measures, Texas averages 60 dangerous heat days each year; by 2050, that number will climb to 115, second to Florida. Human productivity has its limits, a commonality we share with other critters. We often use heat index to help us understand the “feels like” temperatures and dangers outside, but heat index is generally a measure of what it feels like in shade. Another critical concept we need to all get used to is wet-bulb temperature, which uses additional variables like dewpoint and wind speed to infer conditions in direct sunlight—the kinds of conditions many folks work under in outside labor.

One of the first calls I made today was to our friends at Cedar Ridge Preserve, a 600-acre sanctuary in Dallas County managed by Audubon Dallas. The voicemail I received? Due to dangerously high temperatures, and recent rescues of dogs and nature lovers who became heat-stressed on the trails, the preserve had adopted new operating hours, from 6:30 until noon. I decided to check today’s wet bulb reading for Smithville, Texas, where I spend a lot of time outside (as much as I could these past three weeks, and where I’ll be this weekend). Here’s what today’s reading looks like:

That last value, WBGT(F), is the wet bulb reading for today: 91. That number gives us an idea of how easy or difficult it is for the human body to cool itself. Going down a little further, I come to a chart that helps me understand how such a reading may impact me. Sure enough, ideally I’d need to rest every 45 minutes for every 15 minutes of work. Imagine that at scale: over the course of an eight-hour work day I’d need fully six hours of resting to keep myself safe. Now imagine that across an entire outdoor labor force, and consider the implications. No wonder I’ve felt so bad these past few weeks—and I’m just recreating outside, not trying to make a living. What are the implications for our farmers, ranchers, roofers, builders, workers, game wardens, and in general, anybody and everybody who works or plays outside?

As I think about my kids’ future in the great Lone Star State, I think about the present and future Texas in which they will live—one that is already significantly warmer than the world that greeted me in Houston in the 1980’s. The childhood I enjoyed—constantly outdoors, running around my parents’ carefully manicured lawn, constant swimming, exploring Hill Country rivers like the Frio[1] and Guadalupe, baseball, basketball, street hockey, you name it—is already no longer possible, in some ways. The office of the Texas state climatologist at Texas A&M finds that the

- average Texas temperatures in 2036 should be expected to be about 1.6 °F warmer than the 2000-2018 average and 3.0 °F warmer than the 1950-1999 average.

- This would make a typical year around 2036 warmer than all but the absolute warmest year experienced in Texas during 1895-2018.8.

It’s around 1.4 °F warmer these days than it was forty years ago, and by 2036 (fewer than fifteen years out, believe it or not, less than half the time folks buying a house today will have on their [1] typical mortgage), it will be around three degrees hotter, on average, than it was during the time when many of our members and readers were growing up here (with apologies to our young birders). That’s sobering.

Of course, what matters to people also matters to birds, and vice versa—that’s why, in addition to nurturing our souls, birds are such an incredible indicator for whether our natural systems are in balance. Wet bulb temperatures and bird size tend to be correlated, and there are clear connections between sustained heat and hatching success, in Texas and elsewhere. All of us have evolved to manage our environments. As the world’s climate also evolves, our natural systems to thermoregulate will be challenged. Birds, like mammals, are homeotherms, and operate within specific internal body temperatures. One concept that frames how our birds may respond to the changes is sometimes called an “ecological trap”; that is, how an adaptation that is useful in one way may negatively impact another. As temperatures rise and we critters look for conditions that allow us to stay within ranges to which we are accustomed, there are tradeoffs with respect to energy use for thermoregulation and things like reproductive success, for example.

The obvious question, of course, is what can we do about it? Collectively, we’ve got a lot of work to do, and we all can and need to do something useful toward a more sustainable present and future. We at Audubon Texas continue to focus on important ways we humans can change our behavior to reduce consumption and to foster economic opportunities that encourage a lower-pollution future. One initiative we will write about in coming months is around Lights Out Texas, a joint collaboration with Texan By Nature that works with communities to create dark skies during spring and fall migration to lessen bird strikes and mortalities. What does this have to do with temperature? Well, the less energy we consume, the less power we have to generate, which means fewer heat-trapping carbon molecules headed into the atmosphere—and less warming. It’s a win-win. We’re also focused on programs that will help Texans adapt to a warmer place and related stressors, such as changing rainfall patterns, rising seas, reduced soil moisture, and other ecosystem changes. Programs like Audubon Conservation ranching, which continues to expand in Texas, foster opportunities with Texas producers to benefit from bird-friendly rangeland management by fetching a premium price at market; these practices yield other benefits like increased soil moisture retention, greater potential soil carbon sequestration capacity, and more intact and functional habitat. There are no silver bullets, and we are going to have to whittle away at the problem from every corner of society, in every way possible. I’m a strong believer in behavioral change, technology transfer (e.g. fostering the conditions most likely to accelerate sustainable low-carbon solutions at scale at a pace that promotes adoption from the world as fast as possible). Texas can and should lead. There is no time to waste, and there is a lot of money to be made. Texas performs better economically and ecologically under every alternative scenario to reduce carbon compared to business as usual.

[1] On June 22, 2022, the Frio river measure 0.0 cubic feet per second of flow, its lowest reading since September 2011, our last major drought, and in parts of Texas, the drought of record. In other words, no flow.

How you can help, right now

Join Audubon Texas Today

Becoming a member supports our local work protecting birds and the places they need.

Consider a Legacy Gift for Texas

Planned gifts and bequests allow you to provide a lasting form of support to Audubon Texas.

Subscribe to Our Newsletter

Subscribe to our newsletter for updates about Audubon Texas's conservation work, and news about our activities and local events.